|

At present, we are infested in this country with a race of smooth-tongued, worldly-wise Zen teachers who feed their students a ration of utter nonsense. "Why do you suppose Buddha-patriarchs through the ages were so mortally afraid of words and letters?" they ask you. "It is," they answer, "because words and letters are a coast of rocky cliffs washed constantly by vast oceans of poison ready to swallow your wisdom and drown the life from it. Giving students stories and episodes from the Zen past and having them penetrate their meaning is a practice that did not start until after the Zen school had already branched out into the Five Houses, and they were developing into the Seven Schools. Koan study represents a provisional teaching aid which teachers have devised to bring students up to the threshold of the house of Zen so as to enable them to enter the dwelling itself. It has nothing directly to do with the profound meaning of the Buddha-patriarchs' inner chambers."

An incorrigible pack of skinheaded mules has ridden this teaching into a position of dominance in the world of Zen. You cannot distinguish master from disciple, jades from common stones. They gather and sit – rows of sleepy inanimate lumps. They hug themselves, self-satisfied, imagining they are the paragons of the Zen tradition. They belittle the Buddha-patriarchs of the past. While celestial phoenixes linger in the shadows, starving away, this hateful flock of owls and crows rule the roost, sleeping and stuffing their bellies to their hearts' content.

If you don't have the eye of kensho, it is impossible for you to use a single drop of the Buddha's wisdom. These men are heading straight for the realms of hell. That is why I say: if upon becoming a Buddhist monk you do not penetrate the Buddha's truth, you should turn in your black robe, give back all the donations you have received, and revert to being a layman.

Don't you realize that every syllable contained in the Buddhist canon – all five thousand and forty-eight scrolls of scripture – is a rocky cliff jutting into deadly, poison-filled seas? Don't you know that each of the twenty-eight Buddhas and six Buddhist saints is a body of virulent poison? It rises up in monstrous waves that blacken the skies, swallow the radiance of the sun and moon, and extinguishes the light of the stars and planets.

It is there as clear and stark as could be. It is staring you right in the face. But none of you is awake to see it. You are like owls that venture out into the light of day, their eyes wide open, yet they couldn't even see a mountain were it towering in front of them. The mountain doesn't have a grudge against owls that makes it want to hide. The fault is with the owls alone.

You might cover your ears with your hands. You might put a blindfold over your eyes. Try anything you can think of to avoid these poisonous fumes. But you can't escape the clouds sailing in the sky, the streams tumbling down the hillsides. You can't evade the falling autumn leaves scattering spring flowers.

You might wish to enlist the aid of the fleetest winged demon you can find. If you plied him with the best of food and drink and crossed his paw with gold, you might get him to take you on his back for a couple of circumnavigations of the earth. But you would still not find so much as a thimbleful of ground where you could hide.

I am eagerly awaiting the appearance of some dimwit of a monk (or barring that, half such a monk) richly endowed with a natural stock of spiritual power and kindled within by a raging religious fire, who will fling himself unhesitatingly into the midst of this poison and instantly die the Great Death. Rising from that Death, he will arm himself with a calabash of gigantic size and roam the great earth seeking true and genuine monks. Wherever he encounters one, he will spit in his fists, flex his muscles, fill his calabash with deadly poison and fling a dipperful of it over him, drenching him head to foot, so that he too is forced to surrender his life. Ah! what a magnificent sight to behold!

"Don't misdirect your efforts. Don't chase around looking for something apart from your own selves. All you have to do is to concentrate on being thoughtless, on doing nothing whatever. No practice. No realization. Doing nothing, the state of no-mind, is the direct path of sudden realization. No practice, no realization – that is the true principle, things as they really are. The enlightened ones themselves, those who possess every attribute of Buddhahood, have called this supreme, unparalleled, right awakening." People hear this teaching and try to follow it. Choking off their aspirations. Sweeping their minds clean of delusive thoughts. They dedicate themselves solely to doing nothing and to making their minds complete blanks, blissfully unaware that they are doing and thinking a great deal. When a person who has not had kensho reads the Buddhist scriptures, questions his teachers and fellow monks about Buddhism, or practices religious disciplines, he is merely creating the causes of his own illusion – a sure sign that he is still confined within samsara. He tries constantly to keep himself detached in thought and deed, and all the while his thoughts and deeds are attached. He endeavors to be doing nothing all day long, and all the while he is busily doing. But if this same person experiences kensho, everything changes. Although he is constantly thinking and acting, it is totally free and unattached. Although he is engaged in activity around the clock, that activity is, as such, non-activity. This great change is the result of his kensho. It is like water that snakes and cows drink from the same cistern, which becomes deadly venom in one and milk in the other. Bodhidharma spoke of this in his "Essay on the Dharma Pulse": If someone without kensho tries constantly to make his thoughts free and unattached, he commits a great transgression against the Dharma and is a great fool to boot. He winds up in the passive indifference of empty emptiness, no more able to distinguish good from bad than a drunken man. If you want to put the Dharma of non-activity into practice, you must bring an end to all your thought-attachments by breaking through into kensho. Unless you have kensho, you can never expect to achieve a state of non-doing. * Kensho (Chinese: jian xing) is a Japanese term for enlightenment experiences, used in Zen Buddhism. Literally it means seeing one's nature or true self. From http://buddhism.about.com/od/buddhismglossaryk/g/kenshodef.htm:

The kensho experience is a pure realization of shunyata without duality of "seer" and "the thing seen." Kensho is often spoken of as an initial or opening experience of enlightenment that requires further realization and deepening. Douglas Harding labeled Kensho ["seeing my Original (No) Face"] as the 7th step in his Eightfold Plebian Path, with one of the comments being: "I lose my head, but still have to find my heart." He labeled the 8th step of this chart of drawings and comments as Enlightenment. [See www.selfdiscoveryportal.com/arHarding8x8.htm.] In On Having No Head, Harding divided the path into eight more-or-less-arbitrary stages, the 7th being "The Barrier" (i.e., the ego), and the 8th being "The Breakthrough" (i.e., ego death and the revelation that follows).

Articles & Excerpts List |

PSI Home Page |

Self-Discovery Portal

© 2000-2026. All rights reserved. |

Back to Top |

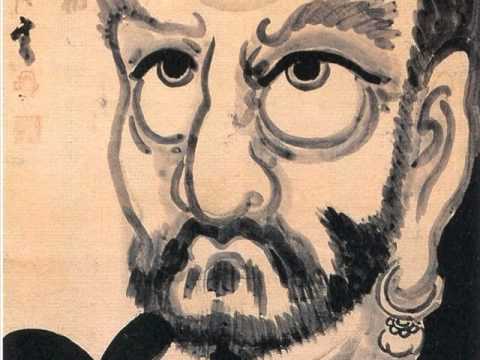

Detail from Hakuin's painting of Bodhidharma (Daruma)

Detail from Hakuin's painting of Bodhidharma (Daruma)